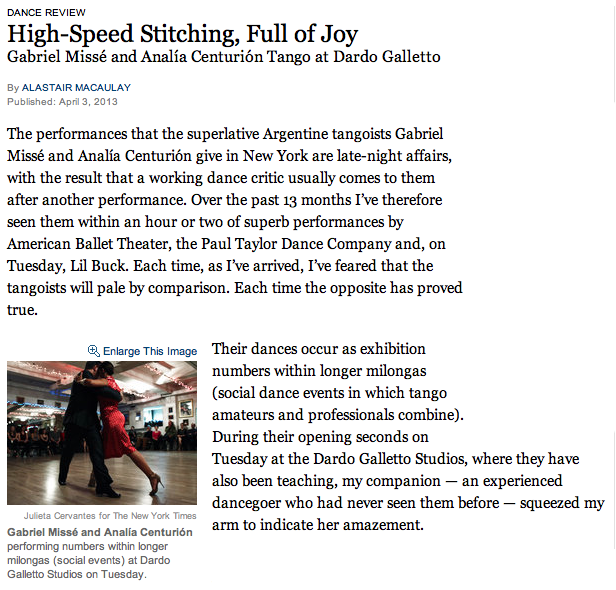

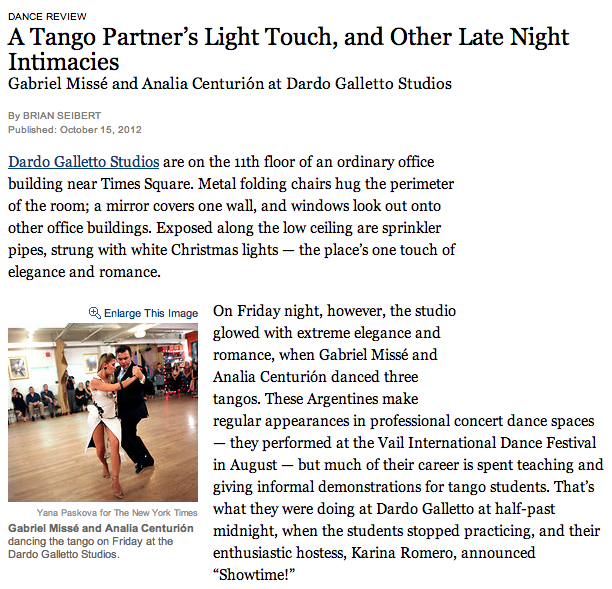

Tango, with the dramatic proximity it gives two dancers from brow to instep and its dramatically weighted walk, can be the most sexually charged of dance forms. It’s romantic, smoldering and very often tragic — as if destiny were steering the couple. But Gabriel Missé, who has been coming regularly to New York since 2008, is all laughter and song. On Saturday night, he was chuckling boyishly around the Dardo Galleto Studios as he prepared the recordings to which he was to dance.

When Guillermina Quiroga (a queen of tango since the last century), wearing a long-sleeved, calf-length dress of emerald green, arrived to join him for their first number, her eyes sparkled with the same laughter as she looked at him from across the floor. For all the audience enthusiasm, no joy in the room could match the delight these two found in each other.

They danced four duets — one more than tango couples usually deliver (the fourth was a sweeping, rapid valse-tango) — all improvised, yet with feats that looked like formal choreography. In their first number, they suddenly knelt at the same moment (a wonderful touch that passed in an instant), and she ended another dance by arriving, in a flash, to sit on his hip.

These exemplary dancers are both Argentine, but their partnership, arranged by Karina Romero, of the Dardo Galletto Studios, is so far exclusive to New York, where they first appeared together in November. They’re ideally matched in physique, temperament and style. Within the opening moments of their first dance, they both showed how many shades of footwork they have: the soft, slow semicircles she traced on the floor with an extended toe (he soon echoed them); the needle turn (one foot pointed into the floor) in which she revolved him; the whiplash strokes of his leg in the air at calf height. At one moment, she released him while he did a single pirouette, within inches of her, before quickly returning to the tango embrace.

The spell of Ms. Quiroga’s style begins in her stance. Often she’s wonderfully high on the balls of her feet, and to watch how, from this narrow base, she then leans forward onto her partner is a marvel. Mr. Missé partners as if he were conducting a happy conspiracy, cheek to cheek; he’s playful in letting his partner turn this way and that, as if she were wriggling in his arms. And both are marvels in tango’s elegant dovetailing of the ankles: Feet are crossed over to make two legs into a single descending triangle.

The virtuosity of both dancers was often breathtaking. An audience of tango connoisseurs shrieked, gasped and cooed at the fast-traveling trills and out-of the-blue pouncing skips. But the beauty of these duets surpassed their bravura. Mr. Missé and Ms. Quiroga make each duet a demonstration of cantilena — the singing legato principle that, in music, shapes the flow of the breath into a flexible and varied current — at its most sensuous. The gorgeous gliding phrases, the hairbreadth pauses, the coloratura flourishes all emanate from the same source.

Tango, for all its theatricality, is intimate — you, me and this music. Saturday’s four duets were acts of private understanding: footwork as chamber music.

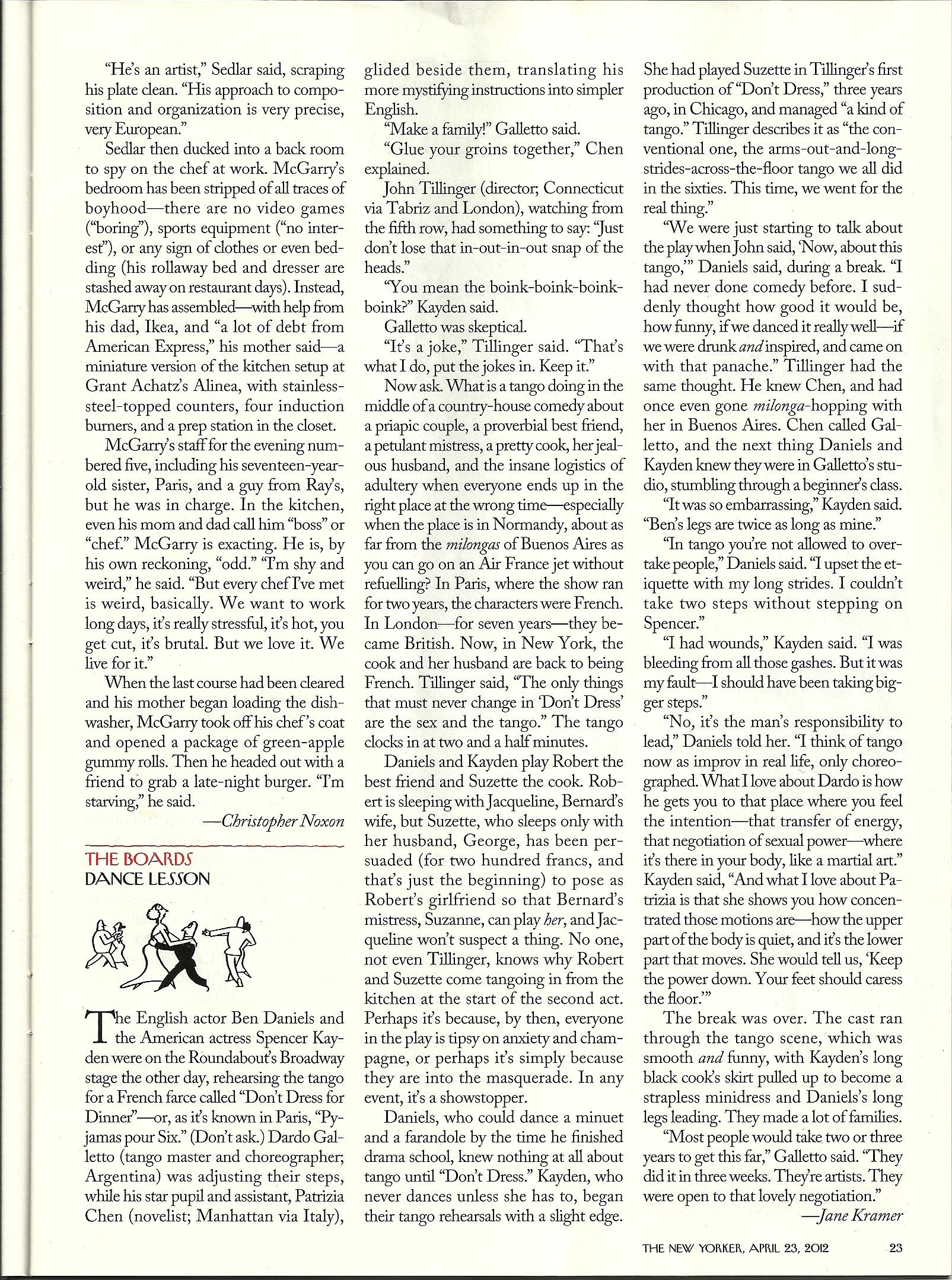

Dance took off in a number of unexpected directions this year. The dance critics of The New York Times — Alastair Macaulay, Gia Kourlas, Brian Seibert and Siobhan Burke — look back at some of the biggest surprises.

Alastair Macaulay

Bournonville Alive A single week in January brought the surprise that the choreography of August Bournonville (1805-79) was alive in the dancing of the Royal Danish Ballet at the Joyce, while the choreography of Marius Petipa (1818-1910) and Lev Ivanov (1834-1901) for the 1895 “Swan Lake” was dead in the dancing of the Mariinsky Ballet. (Another welcome Bournonville surprise was America’s first-ever production of the 1842 three-act “Napoli” with Ballet Arizona: excellent.

Justin Peck’s “Rodeo” The most marvelous new ballet of the year — one of the best of the 21st century to date — had its premiere on Feb. 4 at New York City Ballet. That work, Justin Peck’s “Rodeo: Four Dance Episodes,” was the first and finest of City Ballet’s six 2015 premieres, by Mr. Peckand four other choreographers. One surprise, considerably against the law of averages, is that all six were worth watching. Another is that five showed same-sex and opposite-sex partnering coexisting naturally. The “Rodeo” adagio for five men is a quiet marvel; I hope it proves a classic.

Cunningham Here, Cunningham ThereAll year long, it was happily startling to find how much choreography by Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) was on view, and in good shape. I saw it at New York Live Arts (New York Theater Ballet in “Cross Currents,” February), at the Joyce Theater (“Event” by the Compagnie CNDC Angers in March and “RainForest” with the Stephen Petronio Company in April), at the Peter Jay Sharp Theater (Juilliard Dance in “Biped” in March), at the new Whitney Museum (“Crises” as part of the opening Conlon Nancarrow season in June), and at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, which showed his long-lost 1957 solo “Changeling” both in a newly found 1958 film with Cunningham dancing it and in live performance by Silas Riener.

Tchaikovsky News The year brought two big revelations about the standard Tchaikovsky ballets. In Alexei Ratmansky’s new production for American Ballet Theater, “The Sleeping Beauty” proves significantly different from the “Sleeping Beauty” we’ve known; and, amazingly, the company’s dancers follow Mr. Ratmansky into a detailed period stylewithout high extensions and with faster musicality. And the Russian scholar Sergei Konaev and other Tchaikovsky experts revealed a rehearsal score for the original 1877 “Swan Lake,” explaining at last many mysteries about the classic’s first production.

Tales of Powell and Pressburger The re-release of the often wacky, often excessive, Powell-Pressburger “The Tales of Hoffmann” in March included the astonishments of Moira Shearer’s finest dancing on screen and Frederick Ashton’s brilliant supporting performance.

Classical Bodies At the British Museum, the exhibition “Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art” (March-July) brought multifaceted revelations of the ancient Greeks’ views of the human physique.

Ballroom Shock Since I detest most of what ballroom dancing has become, especially on television, one surprise was that “America’s Ballroom Challenge” (PBS, April) was at all good. Another was that I lost my heart to Artem Plakhotnyi and Inna Berlizyeva.

Small-Screen Plisetskaya When the Bolshoi prima ballerina Maya Plisetskaya died in May, the trove of YouTube films of her proved far more fun than all those innumerable Dying Swans led us to expect.

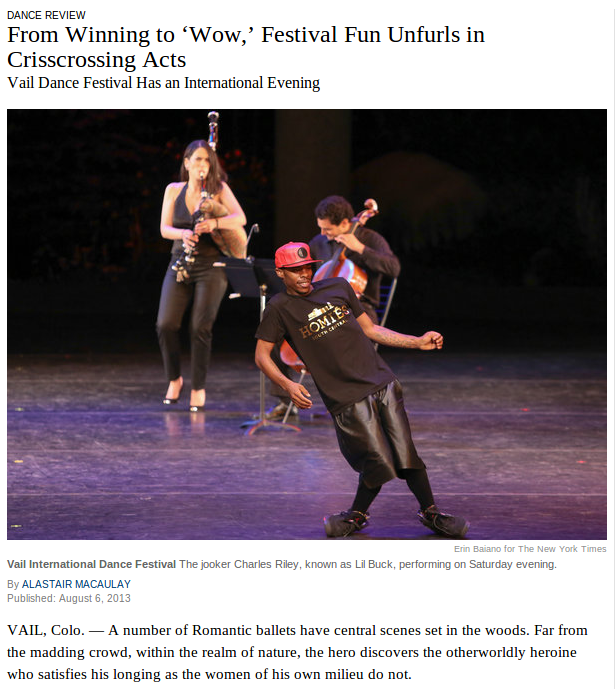

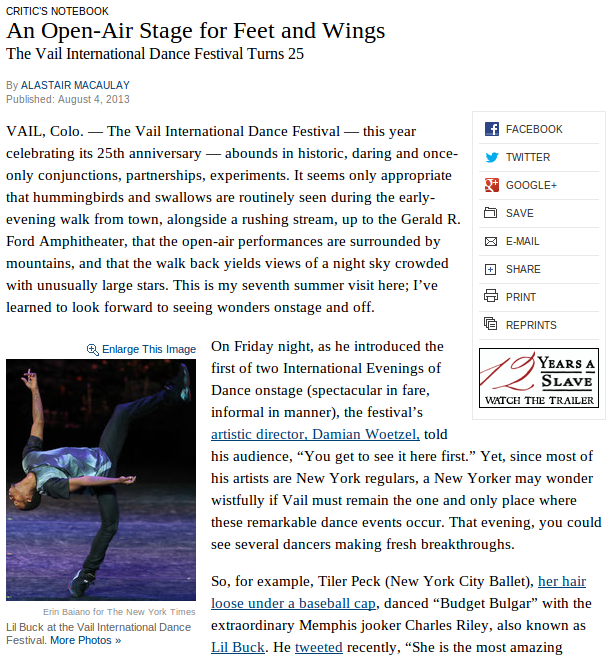

Les Twins “The most famous dancers on the planet!” said the announcement — whereupon it turned out that I had never heard of them. The place was the Apollo Theater in Harlem; the date was Oct. 16; the event was “Breakin’ Convention,” a festival of hip-hop dance theater; and the dancers who arrived onstage were the knockout French fraternal duo Les Twins.

buy cheap isotretinoin online Tango Teaming Two exemplars of Argentine tango, Gabriel Missé and Guillermina Quiroga, danced spectacularly together for the first time anywhere in New York on Nov. 21. The results live on YouTube. More, please.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/13/arts/dance/best-dance-2015.html?_r=0

Tango people keep late hours; I’ve been at gatherings where the best dancers arrive at midnight. For this reason, my tango-watching is limited; I seldom have the stamina. On Saturday, however, I was ready at 11 p.m. at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural and Educational Center in SoHo to watch an event in tango history: Gabriel Missé performing with Guillermina Quiroga for the first time. Excitement among the audience in the packed ground-floor room was intense. The stars did not disappoint; people were calling for more.

In the tango world of Buenos Aires, the pair’s home, Ms. Quiroga is at least as big a name as Mr. Missé has become elsewhere. Each one danced on the same New York program in 2008 (at Symphony Space), but with different partners. She has a marvelously composed persona and memorably elegant posture, especially in the beautiful carriage of her head; it was regrettable that at that 2008 concert she and her partner, Cesar Coelho, used far too many overhead lifts — sensationalism that doesn’t really suit her.

On that occasion, Mr. Missé seemed wholly unlike her. He has famously brilliant footwork; and, though he sometimes lifts his partner so that she can flourish her legs in the air, he almost invariably avoids lifts of any great height. They are both dramatic dancers, but his character has always seemed full of high-comedy wit, whereas hers, in 2008, seemed inclined to Romantic expansiveness.

They performed three numbers on Saturday; all were, we were told, improvised. I have been amazed by improvisations between Mr. Missé and his earlier partners Natalia Hills (2008-10) and Analía Centurión (2012-14), even though they were experienced partnerships. On Saturday, the fluency and speed of give-and-take between Mr. Missé and Ms. Quiroga was wholly astounding.

Perhaps we should call them the Fonteyn and Nureyev of tango. Ms. Quiroga, the older of the pair, has the seemingly more quiet character (her face is masklike even when she’s smiling); Mr. Missé is not only younger but also more outgoing. Nonetheless, the happy revelation of their performance was that she can match his virtuosity point for point, and that he likes that.

In their second number, “Relíquias Porteñas,” he did one of those rapidly skipping pounces, like a thunderbolt from a clear sky, that are among his specialties. She at once replied with one of her own, kicking both heels in the air in a trice. (I remembered how a New York friend of Fonteyn’s went backstage after the first local Fonteyn-Nureyev performance of the pas de deux from “Le Corsaire.” Fonteyn, after joining in the praise for Nureyev’s pyrotechnics, remarked dryly, “I think I held my own, don’t you?”) In their third number, “La Bruja” — a lock of her hair had come loose — she suddenly plunged close to the floor with one knee and rose again, a sudden coup that had people gasping.

They are well matched in both height and physical style. He’s on the short side; she’s petite. Both seem much taller; their dancing projects effortlessly. He wore a black suit and white shirt, black necktie and black shoes; her all-black dress, revealing plenty of thigh at the front, descended to calf length at the back, with silver-white shoes. It was a special pleasure to watch how much of her weight is placed on the extreme front of the foot, to see the clean, swift, cut and thrust of her thigh action, and to feel the easy legato length of phrasing.

He is a coloratura dancer; so, it emerges, is she. The string-of-pearls trills of her traveling footwork — sometimes with feet crossed and ankles tightly dovetailed — sparkled gloriously; and when she brandished a leg in the air and brought it back down, the movement was both glamorous and whiplike. He, earlier, had snapped a foot around his other leg’s shin in a bewildering figure-eight flourish. This was a one-off coupling. Hopes are already high it will not be a once-only.

DANCE REVIEW

It’s Never Too Late to Fall in Love, the Tango Shows

By JACK ANDERSON.

Published: November 21, 1997

Two’s good company. It takes two to tango, and the seven couples in the Argentine company called Tango x 2 danced very enticingly in a program called ”Una Noche de Tango,” which opened a two-week season at City Center on Wednesday night.

The popularity of the tango has increased enormously in recent years, and there are now two tango shows to delight New Yorkers: this one by Tango x 2 and the unrelated ”Forever Tango,” which continues its run at the Walter Kerr Theater.

Tango x 2 set its presentation — conceived, choreographed and directed by Miguel Angel Zotto and Milena Plebs — in a nightspot that changed in ambiance as the evening proceeded. The production, designed by Roberto Almada, showed how over the decades the tango has proved an irresistible temptation to people from many countries and all levels of society.

In both its gritty and polished manifestations, the tango has been an implicitly erotic dance in which the performers’ upper bodies stay cool and collected while their legs and feet do the talking, kicking and swiveling as if making sly innuendoes and, sometimes, passionate propositions. The tango can thrive in dives as well as in posh clubs. But wherever it is found, its footwork is as fancy as the ornamentation on a Baroque palace.

Jorge Ferrari’s neat but never elaborate costumes made most of the dancers in the opening section of the two-part ”Noche de Tango” seem to be working-class couples out for a night on the town. An orchestra, directed by Daniel Binelli, sat on a ledge above the stage, and singers both gathered with the instrumentalists and wandered among the dancers. Unfortunately, wherever they were, the musicians were badly amplified, and some electronic squawks resounded throughout City Center that were not part of the score.

All the performers had strong theatrical presences. That the troupe included both young people and gray-haired performers indicated that the tango can appeal to dancers of all ages. It is never too late to fall in love. But courtship in tango rhythms has its own rules. When a man tried to grasp his partner too roughly in one little dramatic episode, she abruptly left him, as if to demonstrate that passion and decorum must remain partners.

Several scenes were unusual. In one, men danced with other men, as was the custom in some tango clubs earlier in this century. Gabriel Misse and Graciela Porchia and, later, a whole ensemble of dancers offered examples of a form known as the tango waltz, which combines the seductiveness of the tango with the lilt of the waltz. And Mr. Zotto, wearing a gaucho costume, cracked a whip at Ms. Plebs in a duet inspired by the flamboyant tangos danced in silent films by Rudolph Valentino and Natasha Rambova.

When the cast returned to the stage after the intermission, they found that their nightclub had had an elegant facelift. They, too, ascended the social scale, for they appeared in formal attire and elegant gowns. The tango was now the rage of European high society. Steps were refined, especially in a suave duet for Ms. Plebs and Mr. Zotto. But emotions could still take fire, as Gachi Fernandez demonstrated when she wrapped her legs around Sergio Cortazzo in one number; later, in the same piece, he swung her about with glee. And the tango team professionally known as Carlos and Alicia began one dance in a haughty manner, only to grow increasingly uninhibited. Yet no one went out of control.

As a dance of love, the tango is like a game. Everyone associated with Tango x 2 knows the rules and plays the game well.

Photo: Graciela Porchia and Gabriel Misse performing at City Center. (Sara Krulwich/The New York Times)

http://www.nytimes.com/1997/11/21/movies/dance-review-it-s-never-too-late-to-fall-in-love-the-tango-shows.html

Credit Willie Davis for The New York Times

For many people, including me, the word tango conjures the image of a pantherlike milonguero, hair slicked back, in a breathless embrace with a lithe, rapt partner, skirt slit to her thigh, trembling at his every touch. It is the image promoted by big tango shows; the dance becomes a metaphor for Passion with a capital P, rigorously heterosexual and male-dominated, wrapped up in a dynamic of tormented female desire and irresistible male seduction. (Forget that in the early days, men often danced with other men.)

For me, as the American-born daughter of Argentine parents, the situation becomes even more complicated. The first thing many people ask when they hear about my background is, “Do you tango?” The answer is no. No one in my family dances or listens to tango — when my parents were growing up, in the 1940s and ’50s, their parents associated it with the government of Juan Domingo Perón, who had befriended several tango luminaries, most notably the lyricist and composer Enrique Santos Discépolo. Tango was the dominant musical style of the Peronist period, in movies, on the radio. So to me, the Buenos Aires depicted in the songs and dances feels alien, clichéd, hopelessly machista. If you asked me what I thought of the dance, I might point you to the passage in Ezequiel Martínez Estrada’s “Radiografía de la Pampa,” from 1933: It is a “dance of pessimism, of sadness expressed through all the limbs of the body.”

But, no surprise, this image has very little to do with the reality of the tango as it is experienced by those who dance it. What it completely misses is the social function of the milonga — or tango gathering — in Argentina and, since the tango boom of the 1980s, around the world. Like contradance meetups and swing-dance parties, these are places that attract people seeking human contact, creative expression and something as uncomplicated as a bit of fun. Nor does the hackneyed image of the pacing milonguero capture the subtlety and complexity of the dance itself, a kind of conversation expressed through touch, posture and interweaving footwork.

More recently, tango has also moved away from its focus on men leading women around the dance floor. There are other options. Men are dancing with men, women with women; women are leading and men are learning to follow. Often, these roles shift mid-dance.

This liberating and democratizing evolution is largely the product of the Queer Tango movement, conceived by three German dancers — Ute Walter, Marga Nagel and Felix Volker Feyerabend — organizers of the first Queer Tango Festival in Hamburg in 2001. The movement has spread to Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen, San Francisco, Seattle and Rome — and, even in the face of antigay legislation in Russia, to St. Petersburg and Moscow. The Festival Internacional de Tango Queer has been, since 2007, a yearly feature of the dance calendar in Buenos Aires, a city that still has a few hyper-traditional milongas at which men and women sit on opposite sides of the dance floor and women wait patiently to be invited to dance. “I thought they might come after us with torches,” the festival’s co-founder Augusto Balizano said via Skype, “but to my surprise there was a great acceptance among the tango community here.”

New York has not been a leader in the movement, but now, Walter Perez and Leonardo Sardella, partners in life and dance who perform as Malevaje Tango, have taken up the cause. For four days, Oct. 1 to 4, they will preside over their first New York Queer Tango Weekend, which will include workshops by eminent teachers like Graciela Gonzalez (a pioneer in the advancement of women’s technique), dance parties and events like a gala inspired by Rudolph Valentino (black tie required). There was a Queer Tango Festival in New York in 2010, organized by the producer and performer Sergio Segura, but it hasn’t been repeated. “It was too soon,” he said recently. (Mr. Segura hosts Rainbow Tango, a series of open-role tango classes and events at Strictly Tango, the Midtown school he directs. An open house last week included a demonstration by Claudio Marcelo Vidal, the first man to compete at the World Tango Championships in high heels, with his partner, Sidney Grant.)

Mr. Perez and Mr. Sardella hope the weekend will raise awareness about queer tango – also known as open-role tango — and encourage people of all sexual orientations to give it a try. “The tango queer movement was born of a need for people of the same sex to be able to dance together, and we achieved that,” Mr. Perez said recently in his apartment, filled with Peruvian Madonnas, Buddhas, and tango memorabilia, “but it’s one thing to be a minority, one of one or two couples at a milonga; at the festival, we’ll be a majority.”

New York has no L.G.B.T. milonga, even though the city has a lively tango scene, with an average of three dance parties a night. “The fact that you would never be thrown out for dancing with someone of the same sex,” at a conventional milonga, Mr. Perez said, “makes it difficult to create and maintain a gay milonga here.”

At a beginners’ class I attended to learn more about open-role tango, taught by Mr. Perez and Mr. Sardella on a recent Tuesday at the SAGE center for L.G.B.T. seniors in Chelsea, our group learned to walk together to the music, gliding forward, backward, to the side and in a circle without stepping on one another’s toes. I danced with both men and women. As a complete novice, I discovered a slight preference for leading, particularly if I was with a woman of my own size, relishing the chance to choose which direction to take, whether to move in large steps or small, and which moments in the music to accentuate. But following also had its charms: I could close my eyes and simply feel what my partner was asking me to do.

I quickly lost my nerve during a more advanced open-role class at Dardo Galletto Studios, sensing that my rigid fumbling was frustrating my partners’ efforts to get into the zone. In a class of about 10 people, men danced with women, women with other women, but the only same-sex male couple was Mr. Perez and Mr. Sardella, who demonstrated the steps with enviable fluidity and a complete absence of macho posturing.

Many of the women wore high heels and skirts, but Phi Lee Lam, a filmmaker and freelancer from Singapore (“I’ve done everything from gardening to working as a personal assistant”), looked perfectly in her element gliding in blue-and-white saddle shoes and khaki pants, gently maneuvering her partners around the floor. After class, Ms. Lam said she had discovered tango a few years ago on a trip to Buenos Aires when, almost by chance, she had attended a queer tango milonga led by Mariana Docampo. “I just realized this was what I wanted to do,” she told me after class. Back in New York, she started to attend a free community class led by Mr. Perez on Monday evenings at the Brooklyn Library. This, in turn, led her to the class at Dardo Galletto. Ms. Lam prefers dancing with women because, as she put it, “men like to show you what they can do rather than really let go and feel the connection.” For her, the simpler and closer the dancing is, the better.

For a Spanish speaker like me, it’s odd to consider that many of the people who take part in this liberated style of tango cannot understand the melancholy, sometimes downright gloomy lyrics of the songs they are dancing to. (“Let’s drink, for today I need to kill my memories,” Carlos Gardel sings in the classic “Tomo y Obligo.” “I’m not crying for the woman who betrays me, for I know a man mustn’t cry.”) And yet, in a way, they are getting at something more essential. Birthe Havmoeller, a Danish writer and activist who edited a collection of essays on the subject of queer tango (available online), told me via Skype: “There is a sadness in the songs; you dance to get past this sadness into bliss.”

Care to Tango?

NEW YORK QUEER TANGO WEEKEND Oct. 1 to 4; information: nyqueertango.com.

A sampling of classes:

inconclusively DARDO GALLETTO STUDIOS Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. (intermediate) and 8:30 (advanced), open-role tango taught by Walter Perez and Leonardo Sardella; 151 West 46th Street, near Avenue of the Americas; dardogallettostudios.com.

SAGE-NYC Tuesdays at 3:30 p.m., open-role tango for beginners taught by Mr. Perez and Mr. Sardella at this L.G.B.T. senior center; 305 Seventh Avenue, near 27th Street, 15th floor, Chelsea; sageusa.org.

BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY Mondays at 6:30 p.m., free tango for beginners taught by Mr. Perez; 10 Grand Army Plaza, Prospect Heights; bklynlibrary.org.

A sampling of dance parties and milongas:

RAINBOW TANGO Organized by Sergio Segura of Strictly Tango, learnargentinetango.com.

ARGENTINE TANGO A general guide to tango events, newyorktango.com.

Una pareja con vuelo internacional

Desde 2011 recorren el mundo con el tango, recibiendo las mejores críticas.

Milongueros de ley Missé y Centurión tuvieron los mejores maestros.

Hay innumerables caminos que desembocan en el tango. Analía Centurión y Gabriel Missé comenzaron sus trayectorias desde lugares muy diferentes, y sin embargo se encontraron profesionalmente hacia fines de 2008, se reencontraron en 2011 y desde entonces son de manera estable una muy exitosa pareja de baile. Recorren el mundo con su trabajo y son enormemente celebrados en el centro de danza del planeta: Nueva York.

El crítico del New York Times, Alastair Macaulay, se ocupa de la pareja no menos de tres veces por año, y la influyente revista The New Yorker les dedicó una nota especial en 2013. A propósito de un espectáculo presentado el año pasado en el City Center neoyorkino, Missé fue definido por Macaulay como el “Barishnikov del tango”.

Historia de Analía: “Nací en Chacabuco y comencé con el tango a los siete años, a través de la música; poco después empecé con clases de ballet, y gracias a los Torneos Juveniles bonaerenses me formé en el tango de escenario. En 1997, gané la categoría Tango fantasía, y conocí a varios maestros, jurados de las competencias, como Carlos Rivarola y Mingo Pugliese.” ¿Conocías ya el mundo de las milongas?

No. De a poco comenzamos a venir a Buenos Aires con mi compañero de entonces, para perfeccionarnos, como podíamos. Después, nos anotamos en un proyecto que se hacía acá, con maestros milongueros que daban clases de tango de salón a gente joven. Primero, veníamos dos veces por semana; después, cada vez más. En 2004 entramos al show de Copes, me instalé aquí, comencé a viajar, a bailar en casas de tango… y todas las noches a la milonga.

Si la expresión ‘milonguero de cuna’ tiene algún sentido, bien se le puede aplicar a Missé. “A los cuatro bailaba folclore, en la escuela del Chúcaro y Norma Viola; y a los siete empecé a tomar clases de tango, junto a mis hermanos, con Carlos Rivarola. Al poco tiempo, nos llevaba a la milonga.

¿Te parecía raro encontrarte en ese medio de adultos?

Era demasiado chico para darme cuenta. En algunas milongas, un poco más ‘pesadas’, la gente te lo hacía notar. Pero por suerte nos llevó a milongas muy buenas, en las que pude conocer la historia del tango y, más tarde, a los casi últimos milongueros, con los que aprendí mucho.

¿Desde cuándo tu carrera fue profesional?

Desde el principio; mi primera exhibición la hice a los siete años. A los diecisiete estaba con la compañía de Zotto y Plebs en la Bienal de Danza de Lyon. Y un año después, también con ellos, en Nueva York, donde recibí mi cumpleaños dieciocho con una crítica en el New York Times que me destacaba. Apenas bailaba medio vals.

DANCE | DANCE REVIEW

Cheek to Cheek to Cheek

Tango Stars Perform at Dardo Galletto Studios

Three Argentine tango dancers — Maria Blanco, Leonardo Sardella and Walter Perez — danced four duets on Tuesday at the Dardo Galletto Studios in Manhattan. The one-night event was of exceptional interest for several reasons.

The first is simply that Ms. Blanco is among the world’s loveliest dancers, in both physique and style. (I watched these duets an hour after New York City Ballet’s gala had ended, with its top stars still fresh in my memory.) The eye rests on her neck, her waist and, above all, her legs. The way she often rests all her weight on the extreme front of her foot, leaning forward, seemingly way off-balance and yet always secure, is entrancing.

She danced the first and fourth duets with Mr. Sardella: Their partnership had already delighted me on two occasions in August. She also danced the third with Mr. Perez. Both Mr. Sardella and Mr. Perez are handsome, elegant dancers, and the other exhibition number was a duet these men danced together. Each duet had its own sharply distinct mood, with steps that did not recur elsewhere; the variety of the form grew ever more enchanting as you watched.

None of these three offered the bewildering feats of prestissimo coloratura footwork that are now a celebrated feature of the dancing of Gabriel Missé, but there is room in the world for all of them. Indeed, I first spotted Ms. Blanco and Mr. Sardella dancing informally amid the throng at a Dardo Galletto tango gathering (the word for such an event is a milonga) on Aug. 10, while waiting for the star appearance of Mr. Missé and Analía Centurión, of whom I’ve often written with great admiration.

On that occasion, Ms. Blanco and Mr. Sardella were the most informal people present, very much off duty. She wore harem pants, he bluejeans, and both — in a milieu where women almost invariably wear spectacular heels — were in sneakers. And they did no fancy steps. But everything they did was stylish, beautiful, in physical line, and rich in legato phrasing; the exceptional elegance of their dancing hung in the memory even after the marvelous display by Mr. Missé and Ms. Centurión.

When I inquired about their names, Ms. Blanco’s was already known to me; a tango friend had been urging me for two years to watch her dance. Her chief partner, in fact, is Jorge Torres, who, for some connoisseurs, is tango’s quintessence: I hope to see him dance with her one day. Mr. Sardella’s main partner is Mr. Perez. (Same-sex partnering has a long tradition in tango.)

Mr. Perez led on Tuesday, but he danced with Mr. Sardella as if they had found a happy balance of power. The long cheek-to-cheek position of their opening phrases made a marvelous impression, with both faces turned calmly outward. Some explosive back-kicks by Mr. Sardella were wonderfully startling without breaking the flow.

The Blanco-Sardella partnership is “for fun,” they have said, but it’s felicitous. I watched them dance three exhibition numbers — improvised — later in August, as well as the two on Tuesday. Fun was certainly a regular ingredient, but so too were elegance, musicality, romance, wit and serious glamour.

Sometimes Ms. Blanco seems the stronger personality; when she promenades him, your eye is torn between the two. In Tuesday’s final number, the playfulness with which each picked out one bouncing phrase in the music and did tiny, laughing, foot-exchanging jumps (“changements” in ballet) on the beat — she, then he, then both — delighted them as much as it did everybody else at the event. I look forward to seeing much more of all three.

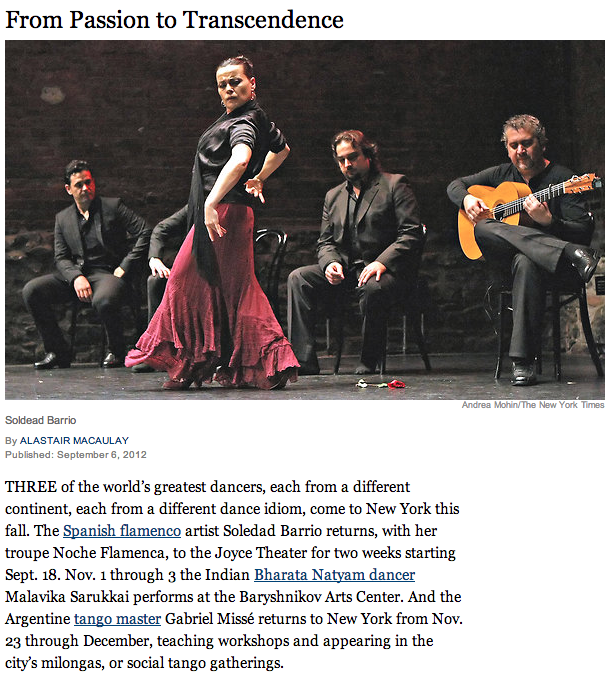

SHALL WE TANGO NYC Festival

October 2014

General Director Polly Ferman, Dance Director Karina Romero, and Master Teacher Dardo Galletto stopped by FOX 5 / MyFoxNY.com Good Day New York to talk about Shall We Tango NYC!

A Good Week: Lil Buck, Mark Morris, Juilliard Dance, Gabriel Misse, and Nrityagram by Marina Harss and comment by Mindy Aloff

Eleven stories above West Forty-Sixth Street, just beyond the glare of Times Square, lies the Dardo Galletto tango studio. Most weekends you can take a class there and then hone your skills at amilonga, a social-dance evening where people switch partners as easily as you can say adiós muchachos. Guest performers, doubling as teachers, come and go from week to week. This week, the Argentine dancers Gabriel Misse and Analía Centurión were in residence. After an hour of watching couples of all sizes and ages grapple with the complexities of tango footwork and partnering, it was Misse and Centurión’s turn. They danced three numbers: a tango (slow, serious), a milonga (fast, lively), and, of all things, an Elvis Presley medley. Misse has attracted quite a bit of attention in recent years; videos of him are all over YouTube, and Alastair Macaulay of the Times is a great fan, but there’s nothing like seeing him in his element. Centurión, attractive, deliciously plump, is a lovely, natural dancer who doesn’t make dramatic tango faces or sex things up unnecessarily. But really, she’s just a foil for Misse, whose dancing is not only elegant and fluid but fanciful and full of witty flights of bravado. He rises onto his toes, he does elegant corkscrew turns, he glides across the floor in tiny steps like millipede. His feet are light and agile, his movements crisp and utterly clear; he caresses the floor or taps it with the very tip of his glossy shoe, interweaving slow, gliding movements with fast, staccato ones. His compact body communicates his intentions with great precision, so that he does not have to call attention to his dominant role as male tango dancers often do. He relays his next move with a light touch, giving Centurión the space and freedom to articulate her own graceful figures. In Misse’s hands, tango becomes less a dance of sex or seduction than a conversation full of charm and joyful interplay, one-sided though it may be. The tango aficionados at the milonga whooped and applauded with pleasure, though I would imagine it must be dispiriting to return to the dance floor after such a display. (I hear they’ll be back in August.)

Marina Harss

Misse and Centurion do more than lead one to admire their skill: They inspire great joy in the audience. Their dancing is more than steps–but more what? While they were in New York, they gave four hard-working days of workshops at the Dardo Galletto Studios. As an observer, I attended one called “Tango Sequences of Famous Milongueros,” for intermediate-level dancers. The first thing one notices about Misse, who conducted the class, with Centurion assisting the students, is how grounded and centered and focused he is. Although his straight-legged stalking walks travel a lot, he uses a great deal of demi-plie in the course of dancing, and he calibrates the depth of it carefully. He also achieves what the greatest dancers alone can, which is to isolate the movement of his legs from the carriage of his torso. (In a performance, this is especially visible in the jitterbug, which, if one were to film him only from the waist up, would present an image of imperturbable gliding, even though, from the waist down, he’s doing crazy-leg rhythms.) Another observer–Nancy Reynolds, research director for The George Balanchine Foundation–was there when I arrived and filled me in on the previous session, in which Misse had lectured in Spanish (with another dancer translating, as would happen in this session as well). “Tango isn’t for fun,” he said in that earlier workshop. “It’s an art.” During the two hours of the “Famous Milongueros” workshop, Misse taught just three steps, three phrases, really–one each for a different milonguero step-author. Several times he cautioned the dancers, “It’s not in the steps,” meaning by “it,” I gathered, the dance. “First, you manage your space,” he told the leaders (some of them were women, as were all the followers), “then, when you have your space, you perfect the step.” The three steps were of increasing levels of difficulty. The first was called “Bird,” because “in this dance, he [the milonguero whose nickname was also “Bird”] looks like he’s flying. You should look like your paragliding.” The phrase is essentially walking, with a wheeling pivot; however, the “flight” is a tiny maneuver at the end, when the follower comes out of the tight phrase with a delicate, almost imperceptible spiral. The second step-phrase, also bearing the nickname of its author (who is still alive, at 86), was the “Small Pear.” “Tango is not an age-related thing,” Misse said. “He’s a very aggressive dancer, but not in a bad way. He’s got a heavy energy.” The “Small Pear” has a kind of story to it, with the follower suddenly challenging the leader by flash-directing her foot toward him, between his legs. The challenge is resolved by the leader taking two tiny, pincering steps inward to frame (or trap) her assertive foot and then shifting his weight so that she can closely pace around him, like a goat edging around a mountain pass. This step embodies that puzzle-solving aspect of tango improvisation that makes it a dance analogy for chess. The third step is called, I believe, “Paralyzed,” to reflect the style of its step-author, also aggressive, yet his dynamism punctuated by sudden pauses. I believe his name was Cachico Mateo la Casa. A spectacular phrase, it begins quietly and works into a rhythm that gives the effect of the leader’s body becoming the handle of a whip and the follower’s body becoming the whip’s responsive lash: Pause together. Walk, walk, flash-flash! This step-author died in 1995, at a milonga, apparently. He asked the orchestra to play his favorite song; disrespectfully, they placed it last. The dancer waited to the end to hear it, sat down after dancing, and expired then and there. Misse also asked the students to listen to a recorded song featuring a singer named, I believe, Ruffino, 16 years old at the time of the recording. “When you hear the phrasing of the singer [on the word “luna,” or “moon”], it’s like walking on the moon.” With Centurion, he demonstrated a dance fragment with the lyric tenderness appropriate to the song. Misse explained that, when he dances to this recording, he imagines himself as the young singer, who had worked so hard to perform at such a young age with a great orchestra. He also said: “The most important thing in this class is not how many steps you learn but that, when you do each step, you’re celebrating the life of the milonguero who made the step. If you do it without life, you’re destroying the work of 60 years.”

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]

[read more at The New York Times]